Table of Contents

An unfortunate by-product of our modern healthcare systems - typically overloaded and under-resourced - is that there's little time for frontline medics to ponder medical ethics. Yet ethical considerations are becoming ever more complex. And that's especially true when medical science today is increasingly able to intervene and change our genetic code.

At the hospital, near the water-cooler on the wards, we discuss a patient with a terminal disease. We're talking about a new therapy, cells being taken out of your body, your own cells changed in the lab, then put back in to fight cancer. It wasn't the first time we had heard about such therapies. But we're talking about it because it was the first time we'd had a patient explain to us about such therapies. They've been in the news a lot recently.

Gene editing has been talked about since the 1960s, but its never been more in vogue. That's thanks to CRISPR-Cas9 and how it's changed medicine forever. CRISPR is part of the genetic system within certain bacteria, and it has a memory that can store sequences of viral DNA when required. Cas9 is a protein, which cuts viral DNA to pieces on request.

Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna were two geniuses who repurposed this natural system to enable researchers to target any genes we like (up to a resolution), and remove them in the lab. Their work built upon others, but it was inspired and practical - all around the world scientists started using CRISPR-Cas9.

Then, in 2018, something happened that made headlines around the world and sent a seismic shock through the genomics community.

He Jiankiu, a Chinese researcher, announced the creation of the world's first gene-edited babies, twins no less. Along with colleagues in the city of Shenzhen, close to Hong Kong, he had secretly used CRISPR, a form of gene-editing technology, to edit the genes of embryos in an IVF clinic.

His goal was to make these twin sisters completely immune to HIV. Their father was HIV positive. The experiments involved forged documents and deceit, and ethical considerations had clearly been thrown out the window. For his role, Jiankiu was incarcerated.

Two years after Jiakiu donned his Chinese prison kit, Charpentier and Doudna were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry, the first ever female-duo to receive one. Their CRISPR-Cas9, or "genetic scissors" as now commonly taught in universities, have changed medicine forever. And their work brought the ethics of gene editing from the realm of hypothetical to the vanguard of reality.

Risks of infections and the rate of relapse remain major challenges. Nonetheless, the global CAR-T cell therapy market size was valued at $4.38B in 2023. It grew 45% last year, and it is projected to grow to $16.35B by 2032.

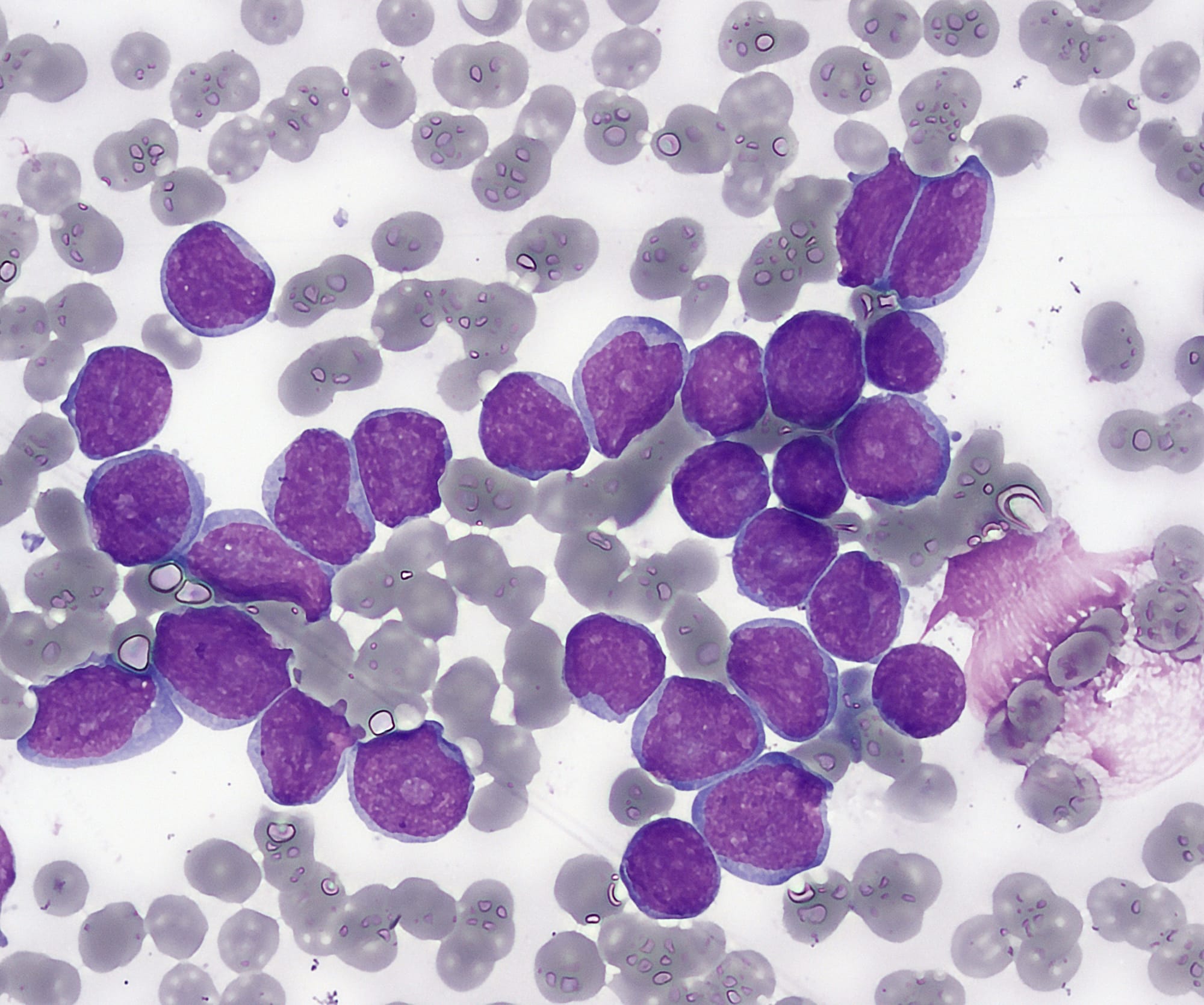

CRISPR-Cas9 is essential in CAR T-cell therapy, which is one of our best hopes for defeating cancer. Novartis was the first to get FDA approval in 2017 for young people with precursor B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. Since then, seven CAR T-cell therapies have been approved, the latest won by Amgen in May this year with TARLATAMAB-DLLE for small cell lung cancer (and only for patients in the extensive stages of the disease). Two of these are Yescarta and Tecartus from Kite, which have just become available on the NHS for treating patients with cancer.

CAR T-cell therapy seemed all the rage in 2023, and then GLP1-agonists became the pharma idols of 2024. CAR T-cell therapies are so impressive, and the potential for the technology is huge. Most importantly, these therapies are already saving lives for patients who desperately want to live. Solid tumors and autoimmune diseases might yield to these therapies too, although the early results have been hit and miss.

There's a chance CAR T-cell therapy might make it to the top of the headlines again next year and I hope they do. Turning cancer patients into cancer survivors is one of the most noble pursuits within this industry.

Despite the excitement around these therapies, there are practical as well as ethical issues. Some treatments can cost half a million USD to extend the life for cancer patients with no other options left. Success rates vary with different cancers and often cancers return.

However, every once in a while, patients do want to know everything about a treatment and to try to weigh up all the risks. With CAR T-Cell therapies, the science is so young, it's difficult to say, and there are many questions we can't answer. Most people don't care whatsoever that their genes are being altered so long as it saves their life. But if they do care about every detail, what might happen, what should we tell them?

In medical school, we swore by the Hippocratic Oath; it is a statement of ethics, intent and purpose attributed to the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates. It has been updated several times to reflect modern practices but at the heart of the Hippocratic Oath - or you might say at its soul - is the phrase "do no harm".

And as evidenced time and again, when technology develops, it does so at an exponential rate. Significant advances in AI and machine learning models will accelerate progress. We may find ourselves in the not-too-distant future in a place that was once the realm only of science fiction. A world where we have the technological ability to edit genes freely, allowing us to change the physical characteristics and biological makeup of an embryo as we please, if society decides to allow it. Blue eyes, or brown eyes? Wavy hair, or straight? Runner, or wrestler? In all of this, what exactly are we treating - and what counts as harm?

The conversations about the rights and wrongs, the benefits and dangers of gene therapy are in danger of lagging behind the research. Whilst there are those who can be over-zealous or unethical in embracing new technology, we already have inspiring figures emerging in the field who are acting as pioneers and role models of progress. It's time for a reasoned, considered debate, joined not just by scientists, but also by patients, politicians, philosophers, and of course physicians. It's a conversation that needs to be had, and had now. Water-cooler chats aren't enough if we're to hold firm to the maxim of that great Greek thinker of two millennia ago, which surely still holds good today - to "do no harm".